October 04,2022

Bernard Wharton

by David Stewart

View Slideshow

The black house perched on a craggy island bluff at the mouth of Narragansett Bay might be seen as the residential design equivalent of dog-bites-man journalism: a story if only in its inevitability. A member of an old East Coast family builds a retreat for himself in a location that for generations was a summer haunt of his forebears. An architect, he fashions the house in the stylistic idiom that his Greenwich, Connecticut-based practice has honed and reinterpreted for over three decades. A lifelong sailor, he incorporates artifacts and decorative elements that evidence an abiding passion for the sea.

Presses, given such sheer aptness, would not be stopped in heralding Bernard Wharton's shingled residence on Rhode Island's southern coast. Except that what he has achieved in its execution is wholly noteworthy: a structure that communicates brio and presence as it diffidently retreats into its natural backdrop, a contemporary building, clearly enamored of the past, whose green virtues all but guarantee its lasting viability.

Once owned by Benedict Arnold, the property is rich in history. Whartons started coming to the wooded island in the 1870s, and it was precisely where the house now sits that Wharton's father, a World War II pilot, would land his private plane on the way home to Philadelphia from postwar air shows. Wharton and his wife, Jennifer Walsh, owned real estate nearby. But when the promontory lot that contained both his favorite childhood swimming spot (for its broad, flat rocks at the water's edge) and an expansive panorama of one of the preeminent coastal channels unexpectedly came on the market, "there was no way," he emphasizes, "it wasn't going to be ours."

Compounding the pressure any architect experiences when acting as his own client was the responsibility Wharton felt toward the site: "I was so grateful to have this sacred little place, so entirely humbled by it, that it was critical I do the right thing with it." He drew perhaps a dozen schemes before settling on a 12-room, 3,800-square-foot design for the building that would be an almost weekly destination for the couple ("Summer houses aren't really summer houses anymore," he points out), their four children and four dogs. Having been influenced early on by the work of 19th-century architect H. H. Richardson, Wharton has long favored the Shingle Style. As the design principal of the firm Shope Reno Wharton, he has produced variations on that model of traditionalism for numerous residences—here, he employed it as the conducive armature for his family's elegantly ordered but casual way of living.

Hemmed on either side by cedars, the long driveway deliberately meanders, so the first thing seen upon arrival is the expanse of blue at the terminus of a lawn that seemingly rolls to the horizon (the infinity-pool effect, Wharton wryly suggests, as applied to landscape). The house, when it does come into view, is framed, its darkness and verticality enhanced, by the trees. As it lies perpendicular to the coastline, its generous size is not instantly revealed: "Conceptually," says Wharton, "the façade, through its shape, deflects your eyes outward and away from itself, the water being the main event."

The color, surprisingly, complies. Not found elsewhere on the island—or in any other residence in his firm's portfolio—black was what Wharton had in mind from the beginning for the house's painted shingles. He enumerates: "From the driveway, you're in high-anticipation mode and don't expect that color at all. From a boat, it's mysterious and intriguing and causes the house to visually recede into the tree line. It combines well with the blue of the ocean and the green of the lawn, and the dark green trim detail crisps it. It's ecologically sound in absorbing the sun's heat in the winter. It's fun."

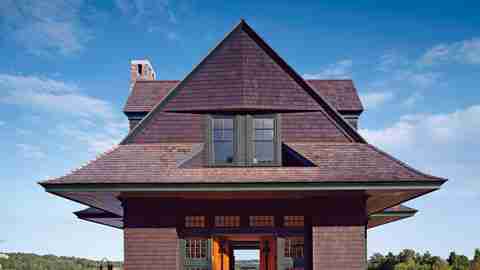

A good time, aesthetically, was also had with the overscale gabled roof. "I've always been fascinated with big, sweeping roofs with exaggerated peaks," Wharton continues, adding that he especially likes an overhang "with a gentle kick at the end, where the Japanese influence really comes through to give the house a sense of lightness." The large overhangs provide shade and vital cooling in the summer months as well as protection in inclement weather. While the roof's massing could have been overwhelming, the fieldstone chimney (which anchors the building), the horizontal cornices, the organic-looking wood brackets of the porch columns and the transparency around the front doors mediate the scale.

The living spaces are essentially a sequential progression through planes—the enfilade begins in a gallery—accentuated by timberwork ceiling frames that reach their full rhythmic potential in the light-infused great room. Reclaimed wood, the dynamic timber members were milled and crafted to Wharton's specifications. The curved "ship's knees" (braces made from tree roots for the deck beams of wood ships) at the opposing dining area and fireplace walls came from the same Maine bogs that produced the knees for the USS Constitution. As an interior device, the timberwork resolves Wharton's desire for a "not too formal but volumetrically and detailing-wise interesting space"; as a soul saver, it joins with the underground irrigation system of recycled water and other such environmentally sensitive features.

Walsh established an interior palette she describes as "what would feel comfortable and correct, what would be calming." The couple selected the furnishings together, with Wharton supplementing their collection with pieces from Connecticut antiques dealers ("If he could get away from the office for an hour, he'd search the shops in town," Walsh says) and those he commissioned: the master bed and a chest of drawers from his design and a set of Blacker House chairs by Greene Greene for the dining area. Most prominent as a décor theme is the maritime assemblage of ship models and paintings. For Wharton, whose genetic pull to the sea results in "near claustrophobia" when he is away from it for any length of time, the nautical elements had to be handled judiciously. "We allude to the ocean often in the house, but we don't go at it in a kitschy or literal way," he says.

The private second floor is, as would be expected, more intimately articulated than the areas below, although there is again the measured pace of an abbreviated enfilade. The primary spaces—master bedroom, two bedrooms, two sleeping alcoves, study—share a Shaker simplicity and play off of the central gallery, which doubles as a library. With its east-facing multipaned window, the master bedroom focuses on the marine tableau to a degree that Wharton has likened it to being on the bridge of a ship.

He wasn't knowingly composing a headline when he chose to have the Antarctic explorer Ernest Shackleton's motto carved into a granite step at the entrance to the house. "By endurance we conquer," however, perfectly captures this particular narrative. "They're a seaman's words that ring very true to me," Wharton says. "Given my history with this place, and the fact that I finally had the opportunity to acquire it—let's just say I've become a great believer in fate." And the terms endurance and conquer, specific to the house? "Every architect knows how difficult it is, and many also know how extremely rewarding it is, to design something for yourself."